The staff of Salt + Light Media come from 14 different countries. This summer, for Canada's 150th anniversary, we are reflecting on what makes Canada so special to each of us. Here Alexander Du, Chief Operating Officer, reflects on his family's Canadian story.

As I read, watch and hear the amazing stories about Canada’s past, and some of its not so proud moments too, I reflect on who I am and where I fit into this Canadian mosaic. I look no further to my father and my mother, their respective origins, how they came to meet and the life they made together for themselves and their children.

My mother, Jeannine Du (nee Beaulieu) was born in St. Boniface, Manitoba. At the time, St. Boniface was home to the largest francophone community outside of the Province of Quebec and was predominantly a Roman Catholic community. The history of Saint-Boniface, effectively founded by the Church, is inextricably linked to Confederation, French language rights and the history of Canada. In 1818, Father Provencher, Father Dumoulin and seminarian Guillaume Etienne Edge arrived in Winnipeg to set up a Catholic Mission east of the Red River. Shortly after their arrival, Catholic schools were also set up and in 1844, the Grey Nuns from Montreal were invited to set up a hospital. This was also the year that Louis Riel was born. Saint Boniface was, in effect, the mother parish for many French settlements in Western Canada and the clergy had an impact and interacted frequently with its main political actors such as Louis Riel.

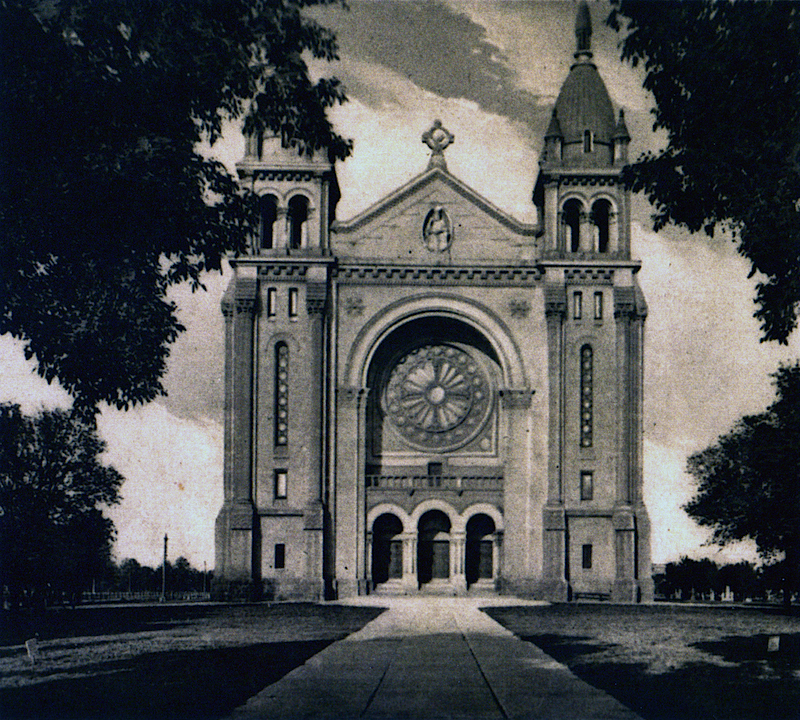

In 1908, this magnificent Cathedral was completed and stood for 60 years before an unfortunate fire burned most of it down. The facade remains and is incorporated into a new Cathedral building.

By 1869, this small francophone fur trading settlement, and the surrounding areas such as St. Norbert, Fort Garry, the Pembina La Salle river crossing, all falling within the Archdiocese of Saint Boniface led by Archbishop Taché, would become the centre stage for a massive struggle between the Manitoba provisional government led by the French speaking Metis and the government of Canada. It is well documented elsewhere how Riel and his French speaking Métis, predominantly Catholic, formed the Manitoba Provisional Government; how they seized Fort Garry during the Red River Rebellion and how the death of John Scott, the North West Rebellion and the subsequent trial and hanging of Louis Riel, helped foster and strengthen an already growing sense of Quebec nationalism in the late 1800’s, and which continues today. These historical events also led the province of Manitoba, only 20 years after joining confederation, to pass legislation in 1890 that altered Manitoba's school system and abolished French as an official language in the province. Due to the demographic makeup of the regional area, which was primarily made up of French speaking Catholics and English speaking Protestants, this legislation was seen as a response to the disputes between French Catholics and English Protestants; a dispute which first arose when Riel rushed to form the Provisional government without including the views and participation of English Protestants. This Act was seen by many as an attack on the rights of both Catholics and French speaking Canadians. Certainly, things have changed over time and French and Catholic schools thrive in Manitoba today but the impact of this tumultuous period of time in the history of Manitoba and St. Boniface also had a lasting direct impact on my mother and the Church in St. Boniface. She told us stories how they would have official English language text books in their desks that they would pull out only when the provincial inspectors would visit their schools and how they would have to stash and hide their the French books on a moment’s notice. Undeterred, the French speaking nuns and clergy of St. Boniface would continue to teach their students in French well into the 1940’s and 50’s until laws became more lax! She also told me of the discomfort she and her mother sometimes felt when they would cross the Provencher bridge into the “Anglo” side of Winnipeg and how they always felt uncomfortable shopping at the big department stores because they were French speaking. Over time, this dissipated but the divide between French and English, Catholic and Protestant was real for many in Winnipeg during my mother’s youth.

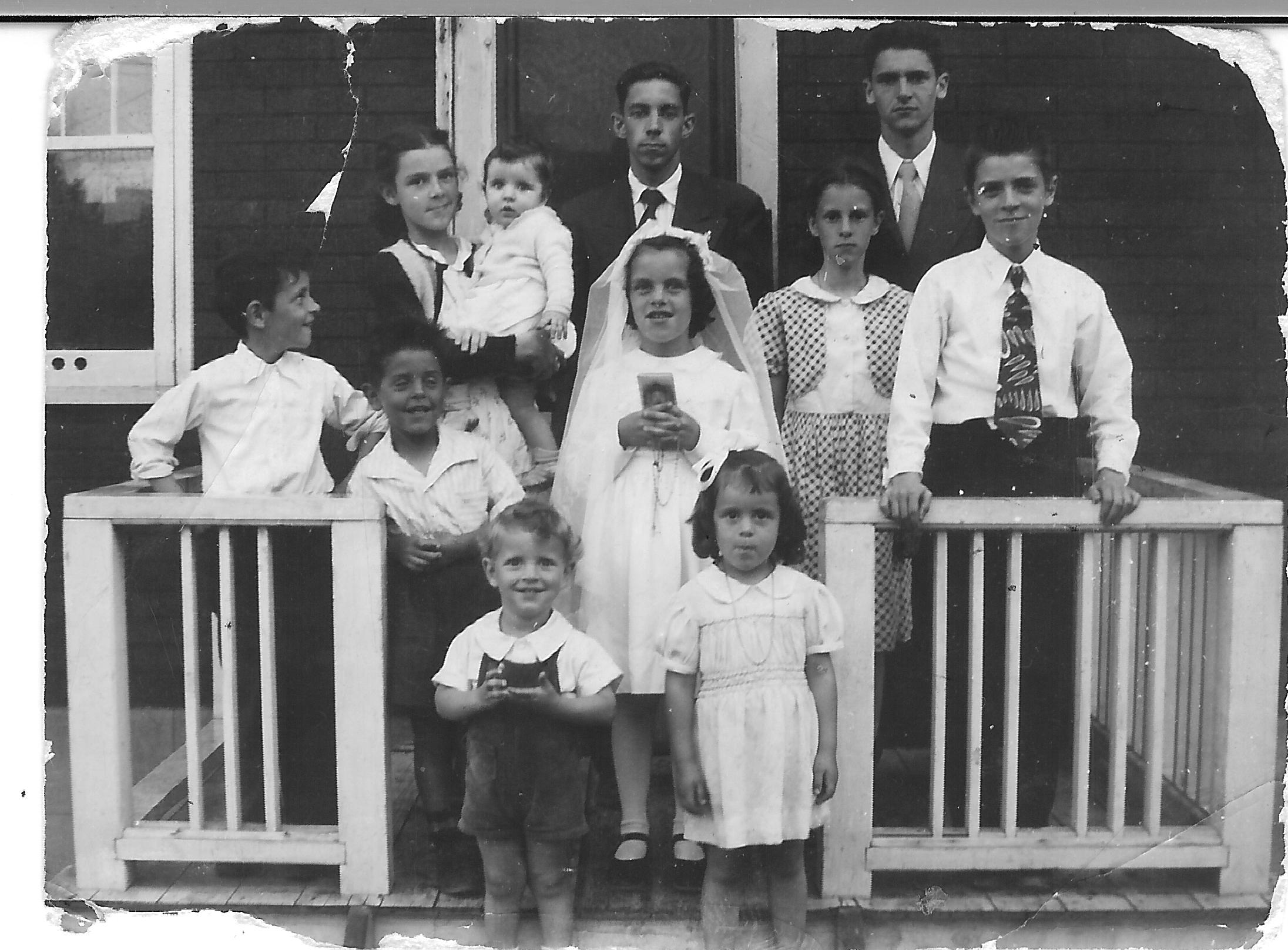

My mother with her 10 siblings after her confirmation.

The Beaulieu family has strong ties to the community, town and archdiocese of St. Boniface; my great great grandparents, Narcisse and Emilie Hudon Dit Beaulieu who are buried in the cemetery on the grounds of St. Boniface Cathedral, arrived in 1881 from Québec and soon they and their children made their mark. Some operated small businesses, others became local tradesmen, or priests or nuns. My grandfather was a carpenter and built many houses in St. Boniface that people still live in today. He also built many church steeples throughout rural Manitoba in the Archdiocese. Over time, the Beaulieu family has found its way into the very fabric of this unique Western Canadian francophone community. The influence and impact of this community and the Church on my mother has certainly touched me and greatly influenced my upbringing as a child.

My great great grandfather (1829-1913)

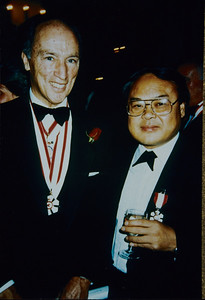

My father, Dr. Joseph Du, immigrated to Canada in 1961 and arrived in Regina to start his internship at the Grey Nun’s Hospital. After spending a year in Regina, he decided to pursue a career in Paediatrics and applied to the Children’s Hospital in Winnipeg. He was accepted and was a resident in Paediatrics from 1963 to 1965. In 1968 he joined the Winnipeg Clinic and started his northern paediatric practice providing medical care and assistance to the children on northern reserves. Sometimes he would fly to these reserves 12 to 18 times a year for over 30 years. In the early 1970’s my father also became involved in the local Chinese community and became part of a team spearheading the revitalization of the Chinatown in downtown Winnipeg. He became the head of the Winnipeg Chinese Development Corporation and the Winnipeg Chinese Cultural and Community Centre, a position he held until he recently passed away. During that time, he also worked on numerous projects and initiatives such as lobbying the federal government to apologize for the Chinese Exclusion Act and the head tax, commemorating Chinese railway workers and their contribution to building unity in Canada by commissioning statutes and exhibits in the Canadian Human Rights Museum in Winnipeg and sitting on the Council for Canadian Unity. During his 56 years in Canada, he worked tirelessly for his patients, for the Chinese community and all Canadians, building bridges, creating opportunity and hope for youth and taking care of old and sick. We didn’t see our father as much as perhaps most people did. Between all the volunteer work, travel up north to reserves and his full medical practice he was as busy as you can be but he always found the time for the important things like having dinner as family almost every night, being present at the birth of every one of his nine grand children and being there for our sports and academic accomplishments.

My father standing in front of the Chinese railroad exhibit at the CMHR, a gift from the Winnipeg Chinese Cultural and Community Centre

Why did a recent immigrant put so much back into Canada? In large part gratitude and a desire to help others.

In the first 18 years of his life, my father had seen much tragedy. He grew up in a world of bombs and bloodshed. Early in his life, he saw firsthand French soldiers suffer great harm at the hands of the occupying Japanese army in Vietnam. When he was eight years old, his father was killed by US bombs who were bombing Japanese ships in Haiphong harbour. Once his father died, his father’s business partners all denied the family his share so my grandmother and her children went from riches to rags overnight. He lost his father and saw his liberty and security fall apart due to war, destruction and greed; where pain and suffering were a common daily occurrence and hardship the norm, he felt fortunate, almost guilty, for being in Canada. This gratitude began when he was successful in getting a scholarship to study in Taiwan. None of his older brothers were afforded this kind of opportunity and they all encouraged him to go. However, as an 18 year old student in Taiwan, away from his family who remained in Vietnam, he was alone and scared. Thankfully, he told me, that he met a a Jesuit, Fr. Jacques Bruyère, who invited him to join a Catholic student group and from there he met many people, developed long lasting friendships and an awareness and appreciation of what it is to be Catholic. He was always grateful to Father Bruyère. From there, things get better for him, but he never forgot what he lived through before getting to Taiwan.

Studying hard in Taiwan. HIs first language was Cantonese but in Taiwan, medical school was taught in English and Mandarin. He told me he studied for many hours every day using 3 translation dictionaries. It was very difficult to keep up.

This gratitude he felt for being able to leave a war torn country fuelled his efforts to bring all of his living brothers to Canada. This gratitude and good fortune is what fuelled his desire to make Canada an even better place than the one he arrived to in 1961. He decided that he would not take Canada for granted and that he must try to make things better for him, his family and other immigrants like him. I suppose this is why he became so heavily involved in assisting and placing Vietnamese refugee families in Winnipeg during the 1970s. He knew so well from personal experience that in a flash, all of your money, physical belongings and physical safety can disappear or be threatened . I suppose he felt that sometimes people need love, care and compassion in their life to help them get to a better place. The same love, care and compassion that he received in his life. Although he never said that to me, I have to think he thought that way because he certainly lived his life that way.

My father was instrumental in securing the land and funding to build a new senior's residence in the heart of Winnipeg's Chinatown, housing that was seriously needed.

One moment that I remember quite well growing up with my father is the day that Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau re-patriated the Constitution in 1982 and enshrined the Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms. I remember my father bringing home a book with the Constitution and Charter in it commemorating this historic moment. It had a real and everlasting impact on my father because I think it meant the validation and protection of multiculturalism. A validation and acceptance of his identity as well as the identity of other Chinese people in Canada; that Chinese Canadians had a place in this country.

At the reception after receiving the Order of Canada, my father shares a moment with Pierre Trudeau.

During his time as a resident, my father met my mother, Jeannine Helene Beaulieu. My mother was an x-ray technician working at Misericordia Hospital. It was there that she met a dashing young Chinese doctor. I can’t even imagine what it must have been like for a French Canadian woman to date and then marry a Chinese immigrant back in the early 60s. My grandfather, Joseph Beaulieu, according to my mother, was fiercely protective and supportive of their relationship. It leaves me with an awe and respect that they had such courage and allowed love to overcome and possible hatred, racism or bigotry.

My father passed away on March 19, 2017. He was only a few weeks shy of his 54th wedding anniversary. The union between my father and mother, I believe, was touched by the Holy Spirit. When my father and mother tried to get married at St. Boniface Cathedral, they were denied on the basis that my father did not have his baptismal certificate. He did not know how to go about getting that from Asia and he and my mother worried and wondered what to do next. One day while my mother and father were out, a finger tapped my father’s shoulder. When he turned around, to his surprise, it was Fr. Bruyere who he met in Taiwan and joined his youth group. When my father and mother told Fr. Bruyere of their predicament, he went into the Archdiocese’s office and vouched for my father’s baptism, and voila, they were to be married in the Cathedral! Fifty-four years later, my father passed away and it was St. Boniface Cathedral where his funeral mass was celebrated by Fr. Thomas Rosica.

My father and mother, just married, leaving St. Boniface Cathedral.

So, in the end, my parents with their shared faith and diverse backgrounds taught me and my siblings what it is to be truly Canadian. We are a family that reflects both the history and future of Canada. We are a family that embodies the spirit of multiculturalism. We are witnesses of their faith and the love they shared with each other, our community and to Canada. My sisters and I, Catholics born with deep French Canadian roots and new Chinese Canadian roots, were taught by the example of our parents to act, think and love like Christ. It is now up to us to do the same.