Keeping the X in Xmas

Kristina Glicksman

Thursday, December 20, 2018

A memory

Driving through the neighbourhood on a frosty winter evening admiring the festive lights and lawn ornaments, I write on the misty car window with my finger: MERRY XMAS. My mother takes advantage of this teaching moment to explain that I shouldn’t write “XMAS” because the purpose of the X is to remove Christ from the picture. I protest that there isn’t enough room to write “Christmas”. But who wants to risk offending God and calling down the scorn of one’s neighbours? So for years I squeezed the full nine letters into impractically narrow calendar boxes. Until I discovered that the X in Xmas is not an X at all.It’s all Greek to me

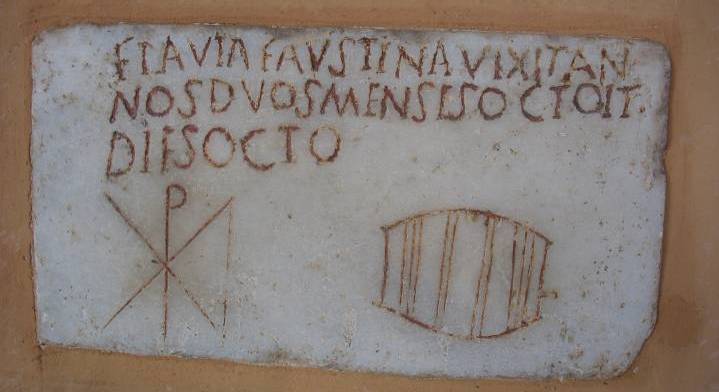

It all goes back to ancient times when a new religion was spreading like wildfire across the eastern part of the Roman empire, a part of the world where the common language was Greek. This new religion preached the resurrection of a man named Jesus, called the Christ by his followers. Or as it’s written in Greek: Ιησους Χριστος – or ΙΗΣΟΥΣ ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ, if you prefer to write in capital letters. Now, I don’t know the exact details of who started using what when, and I don’t think there’s anyone who does, but there is a long history there, and it seems to me that in recent times we Christians have been letting go of our ancient heritage so much that we don’t even know it when we see it. Since the early days of Christianity (well, at least since the late 100s AD, though it might go back further), Christians have been using the Greek letters of Jesus’ name both as an abbreviation and as an expression of piety. Have you ever been in a church or a cemetery (or even a museum) and seen a funny symbol that looks like a P with an X over it? Or something like a dollar sign with three vertical lines? If you haven’t before, I’m sure you’ll notice them now. These are two popular versions of the long Christian tradition of creating monograms from the Greek version of Jesus’ name. They even have a special name: Christogram.

4th-century funerary inscription with Chi-Rho Christogram for Flavia Faustina, who died at age 2 years, 8 months, and 8 days. This inscription can be seen by visitors to the Basilica of St. Paul Outside the Walls in Rome. (Photo credit: Kristina Glicksman)

But the internet tells a different story

There are other explanations for IHS floating around: In His Service or In Hoc Signo (Latin for “by this sign” – a reference to a dream by the Emperor Constantine) or, for the conspiracy theorists, Isis Horus Set. But these all come from another fine human tradition: making up answers for things we don’t understand. Even those who recognize the Greek origin often assume that they simply represent the first three letters of Jesus’ name. And most people are content with that explanation. But if your mind has a more pedantic bent like mine, then walk with me just a little further. (The rest of the class may be dismissed.)

Even those who recognize the Greek origin often assume that they simply represent the first three letters of Jesus’ name. And most people are content with that explanation. But if your mind has a more pedantic bent like mine, then walk with me just a little further. (The rest of the class may be dismissed.)

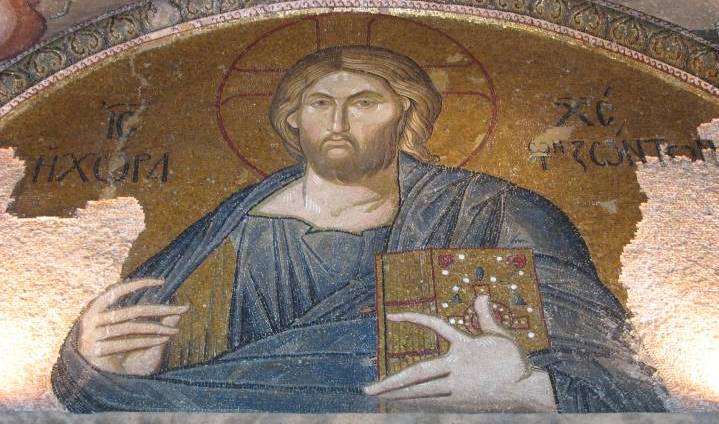

Writing the Bible

In Greek manuscripts of the New Testament, going all the way back to the earliest ones we have dating to around the year 200, the name of Jesus Christ is abbreviated as IC XC – just like you see on Orthodox icons – or IHC XPC. (Don’t get confused by the C. It’s just one way of writing the Greek letter sigma.) When scribes started to copy out the texts in Latin, they kept the tradition of abbreviating the names and even kept the Greek letters.

Mosaic from the Church of St. Saviour in Chora, Istanbul (Photo credit: Kristina Glicksman)

See for yourself

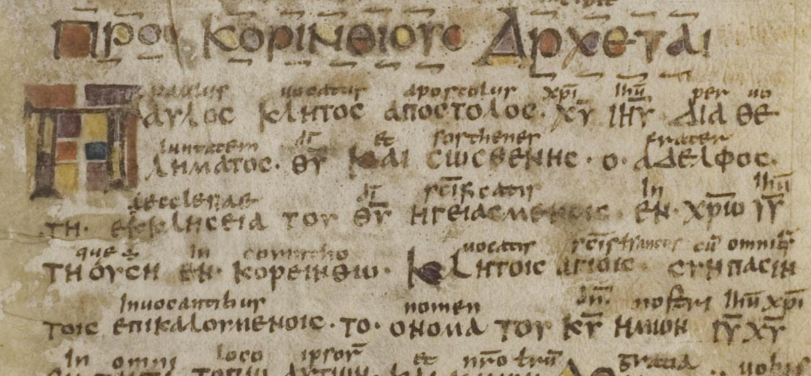

For example, St. Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians begins: “Paul, called to be an apostle of Christ Jesus by the will of God.” Because of the way “Christ Jesus” functions in this sentence, the Greek version of his name (Χριστος Ιησους) turns into Χριστου Ιησου. And the Latin (Christus Iesus) becomes Christi Iesu. Check out the image below of this very verse from the wonderful ninth-century Codex Boernerianus – a Greek text with the Latin words written above for easier reading. Can you see all the places where the names of Jesus are abbreviated? (Hint: the 1st, 3rd, and 5th lines under the title.) And as a bonus, see if you can find the ampersand (Hint: look at the Latin) and the abbreviations for God (Hint: God in Greek is Θεος.)

The beginning of the First Letter of St. Paul to the Corinthians from the Codex Boernerianus. Courtesy of Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek, Dresden.

Related Articles:

<<

SUPPORT LABEL

$50

$100

$150

$250

OTHER AMOUNT

DONATE

Receive our newsletters

Stay Connected

Receive our newsletters

Stay Connected