Saints and their furry and feathered friends

Kristina Glicksman

Saturday, October 3, 2020

St. Gregory the Great tells us in his Dialogues (II.8) that St. Benedict of Nursia had a raven (some translations call it a crow, but I prefer raven) that would visit him every day at dinner time to be fed from the hand of this great Father of Western Monasticism. One day, an enemy, envious of the saint’s holy reputation, sent him a gift: a loaf of bread which he had poisoned. Benedict, knowing the loaf was tainted, ordered the raven to carry it away to someplace where it could do no harm. The bird obeyed and returned some hours later to receive his usual supper. Still today, the raven is a symbol of St. Benedict and can be found on his medal.

One loaf or two?

Another holy man who had a raven friend was St. Paul the Hermit. Credited with being the first Christian hermit, he lived in a cave in Egypt for many decades during the 3rd and 4th centuries AD,

St. Gregory the Great tells us in his Dialogues (II.8) that St. Benedict of Nursia had a raven (some translations call it a crow, but I prefer raven) that would visit him every day at dinner time to be fed from the hand of this great Father of Western Monasticism. One day, an enemy, envious of the saint’s holy reputation, sent him a gift: a loaf of bread which he had poisoned. Benedict, knowing the loaf was tainted, ordered the raven to carry it away to someplace where it could do no harm. The bird obeyed and returned some hours later to receive his usual supper. Still today, the raven is a symbol of St. Benedict and can be found on his medal.

One loaf or two?

Another holy man who had a raven friend was St. Paul the Hermit. Credited with being the first Christian hermit, he lived in a cave in Egypt for many decades during the 3rd and 4th centuries AD,  where he was fed by a raven which brought him half a loaf of bread each day (sounds a bit like the story of Elijah in 1 Kings 17:2-5). Then one day, so the story goes, the raven brought him a whole loaf of bread. Lo, and behold, a guest arrived: another famous hermit by the name of Anthony.

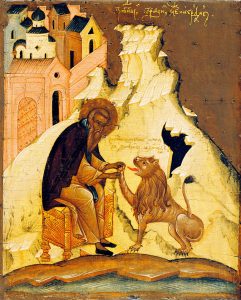

St. Jerome tells us that Paul died soon after, to Anthony’s great sorrow. But then he witnessed something astonishing. Two lions came bounding out of the desert, mourned at the body of the holy hermit, and then proceeded to dig his grave with their great paws.

The lion’s paw

where he was fed by a raven which brought him half a loaf of bread each day (sounds a bit like the story of Elijah in 1 Kings 17:2-5). Then one day, so the story goes, the raven brought him a whole loaf of bread. Lo, and behold, a guest arrived: another famous hermit by the name of Anthony.

St. Jerome tells us that Paul died soon after, to Anthony’s great sorrow. But then he witnessed something astonishing. Two lions came bounding out of the desert, mourned at the body of the holy hermit, and then proceeded to dig his grave with their great paws.

The lion’s paw

Speaking of St. Jerome and lions, he himself has a famous story whereby a lion entered his monastery, sending all the monks fleeing in terror. Jerome, however, noticed that the lion seemed to be in pain. Approaching the animal, he removed a thorn from its paw and earned himself a friend for life.

It was been suggested that since there is a similar story attributed to a somewhat contemporary saint named Gerasimus,

Speaking of St. Jerome and lions, he himself has a famous story whereby a lion entered his monastery, sending all the monks fleeing in terror. Jerome, however, noticed that the lion seemed to be in pain. Approaching the animal, he removed a thorn from its paw and earned himself a friend for life.

It was been suggested that since there is a similar story attributed to a somewhat contemporary saint named Gerasimus, confusion by the author of the 13th-century Golden Legend caused the similarly named Jerome (in Latin, Hieronymus, and later, Geronimus) to be credited with this kindly act despite his otherwise fiery temperament. So hardly anyone remembers Gerasimus now (at least in the West), while for hundreds of years, art has been created depicting Jerome with his feline friend (though artists often struggled with what a lion actually looked like) – indeed it is the surest way to recognize him!

A wolf in donkey’s clothing

St. Jerome and St. Gerasimus were not the only saints to make such unlikely friends among the Lord’s more carnivorous creations.

There were once two Benedictine monasteries in Normandy, France: Jumièges for the monks and nearby Pavilly for the nuns.

confusion by the author of the 13th-century Golden Legend caused the similarly named Jerome (in Latin, Hieronymus, and later, Geronimus) to be credited with this kindly act despite his otherwise fiery temperament. So hardly anyone remembers Gerasimus now (at least in the West), while for hundreds of years, art has been created depicting Jerome with his feline friend (though artists often struggled with what a lion actually looked like) – indeed it is the surest way to recognize him!

A wolf in donkey’s clothing

St. Jerome and St. Gerasimus were not the only saints to make such unlikely friends among the Lord’s more carnivorous creations.

There were once two Benedictine monasteries in Normandy, France: Jumièges for the monks and nearby Pavilly for the nuns.  In the early days of the monasteries, so the story goes, in the 7th century, the nuns used to do the monks’ laundry. To help them in this task, they had a clever, hard-working donkey which would go between the monasteries all by itself with the loads of laundry.

One day, a wolf killed and ate the donkey. When the abbess, St. Austreberthe, discovered the deed, the wolf meekly confessed his guilt, and she commanded him to make reparation by taking the donkey’s place. This the wolf obediently did to the end of his life.

A horse is a horse, of course, of course, unless…

A somewhat similar story is told about St. Corbinian, the 8th-century evangelizer of Bavaria. While he was on his way to Rome, a bear emerged from the forest and killed his pack horse.

In the early days of the monasteries, so the story goes, in the 7th century, the nuns used to do the monks’ laundry. To help them in this task, they had a clever, hard-working donkey which would go between the monasteries all by itself with the loads of laundry.

One day, a wolf killed and ate the donkey. When the abbess, St. Austreberthe, discovered the deed, the wolf meekly confessed his guilt, and she commanded him to make reparation by taking the donkey’s place. This the wolf obediently did to the end of his life.

A horse is a horse, of course, of course, unless…

A somewhat similar story is told about St. Corbinian, the 8th-century evangelizer of Bavaria. While he was on his way to Rome, a bear emerged from the forest and killed his pack horse. Corbinian ordered the bear to carry the horse’s load but released the animal from his service once they reached Rome.

The saddled bear is a symbol of the German city of Freising and its diocese, and when Joseph Ratzinger (now Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI) became Archbishop of Freising-Munich, he included it in his coat of arms.

(As a slight side note: Pope Benedict is well known for his great love of cats!)

Oh deer

St. Giles was a popular saint in the Middle Ages who famously had a pet deer, from whom he received milk to supplement his sparing, vegetarian diet as a hermit living in the woods. One day when the local king was out hunting, he came across the holy hermit’s companion and gave chase. The deer ran home, and when the king tried to shoot her, the arrow struck St. Giles instead, laming him for life. For this reason, St. Giles is the patron saint of people with physical handicaps (among many others!).

Corbinian ordered the bear to carry the horse’s load but released the animal from his service once they reached Rome.

The saddled bear is a symbol of the German city of Freising and its diocese, and when Joseph Ratzinger (now Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI) became Archbishop of Freising-Munich, he included it in his coat of arms.

(As a slight side note: Pope Benedict is well known for his great love of cats!)

Oh deer

St. Giles was a popular saint in the Middle Ages who famously had a pet deer, from whom he received milk to supplement his sparing, vegetarian diet as a hermit living in the woods. One day when the local king was out hunting, he came across the holy hermit’s companion and gave chase. The deer ran home, and when the king tried to shoot her, the arrow struck St. Giles instead, laming him for life. For this reason, St. Giles is the patron saint of people with physical handicaps (among many others!).

Smallest of all

Smallest of all

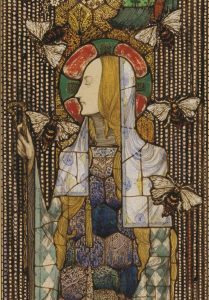

St. Gobnait was a holy woman of Ireland who had a special relationship with bees. So much so that she is the patron of bees and beekeepers. But it wasn’t only honey and wax she received in return for her care of her diminutive friends. Legend says that she once drove away a marauding band of cattle raiders by siccing her bees on them.

Bees, by the way, have a particular significance in Celtic lore as symbols of the soul, so St. Gobnait’s closeness to these busy creatures also has a spiritual significance.

Saint’s best friend?

St. Gobnait was a holy woman of Ireland who had a special relationship with bees. So much so that she is the patron of bees and beekeepers. But it wasn’t only honey and wax she received in return for her care of her diminutive friends. Legend says that she once drove away a marauding band of cattle raiders by siccing her bees on them.

Bees, by the way, have a particular significance in Celtic lore as symbols of the soul, so St. Gobnait’s closeness to these busy creatures also has a spiritual significance.

Saint’s best friend?

Lastly, we turn to a more traditional human-animal relationship.

St. Roch is another saint who was very popular in the Middle Ages. He is usually depicted revealing a wound on his leg and with a dog at his side. St. Roch lived in Italy in the 14th century, during the time when the bubonic plague was ravaging Europe. He devoted himself to the care of plague victims until one day he began to experience symptoms of the disease as well. He withdrew into the forest to die, and there he was visited by a dog which brought him bread and licked his sores until he recovered.

But what, I hear you ask, about those gentle mountain dogs with that holy name, famous for bringing aid to travellers in distress? Surely there must be some story of saintly companionship there?

Sadly not. The St. Bernard breed only dates to the 17th century, while their namesake lived in the 11th. St. Bernard of Montjoux (or Menthon) founded two hostels in dangerous passes of the Alps regularly used by pilgrims to Rome. These passes came to be known as the Great St. Bernard Pass and the Little St. Bernard Pass. The monks who have maintained the hostels since that day eventually enlisted the aid of dogs to help them look after travellers who lose their way on the treacherous and snowy paths. Naturally, this new breed came to be called the St. Bernard, and considering the work they have done in saving countless lives, that name seems well deserved.

Lastly, we turn to a more traditional human-animal relationship.

St. Roch is another saint who was very popular in the Middle Ages. He is usually depicted revealing a wound on his leg and with a dog at his side. St. Roch lived in Italy in the 14th century, during the time when the bubonic plague was ravaging Europe. He devoted himself to the care of plague victims until one day he began to experience symptoms of the disease as well. He withdrew into the forest to die, and there he was visited by a dog which brought him bread and licked his sores until he recovered.

But what, I hear you ask, about those gentle mountain dogs with that holy name, famous for bringing aid to travellers in distress? Surely there must be some story of saintly companionship there?

Sadly not. The St. Bernard breed only dates to the 17th century, while their namesake lived in the 11th. St. Bernard of Montjoux (or Menthon) founded two hostels in dangerous passes of the Alps regularly used by pilgrims to Rome. These passes came to be known as the Great St. Bernard Pass and the Little St. Bernard Pass. The monks who have maintained the hostels since that day eventually enlisted the aid of dogs to help them look after travellers who lose their way on the treacherous and snowy paths. Naturally, this new breed came to be called the St. Bernard, and considering the work they have done in saving countless lives, that name seems well deserved.

Image credits:

Image credits:

- St. Benedict: Medal of St. Benedict executed in stained glass at St. Benedict’s Catholic Church in Chesapeake, Virginia. Photo credit: Nheyob on Wikimedia Commons, used under the terms of license CC BY-SA 4.0

- St. Paul the Hermit: St. Paul the Hermit by Carlo Dolci (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

- St. Jerome: Saint Jerome in His Study by Jan van Eyck (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

- St. Gerasimus: 16th-century icon of St. Gerasimus and the lion (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

- St. Austreberthe: Stained glass window from a chapel in the village of Sainte-Austreberthe in the Seine-Maritime department of Normandy, France. Photo credit: Hélène Dumur on Wikimedia Commons, used under the terms of license CC BY-SA 3.0

- St. Corbinian: Detail of the Altar of St. Corbinian by Friedrich Pacher from the Church of St. Corbinian in Assling, Austria (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

- St. Giles: Illumination depicting St. Giles and his deer from a French manuscript of Vincent of Beauvais’ Speculum historiale. (Source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France)

- St. Gobnait: Detail of a design for a stained glass window in Honan Chapel in Cork, Ireland, by Harry Clarke (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

- St. Roch: Painting of St. Roch from the Portuguese School, 18th century (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

- St. Bernards: To The Rescue by John Emms (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Related Articles:

Category: Saints and Blesseds

Tag: animals, St. Anthony the Great, St. Austreberthe, St. Benedict, St. Corbinian, St. Francis of Assisi, St. Gerasimus, St. Giles, St. Gobnait, St. Jerome, St. Paul the Hermit, St. Roch

Pope’s General Audience – February 5, 2025

Wednesday, February 5, 2025

Pope Francis

Pope Francis

In his Wednesday General Audience, Pope Francis continued this cycle of catechesis on "Jesus Christ our Hope," as part of the Jubilee 2025. This week he reflected on the Magnificat, the Virgin Mary's Song of Praise after she is greeted by her cousin Elizabeth.

Pope’s General Audience – January 29, 2025

Wednesday, January 29, 2025

Pope Francis

Pope Francis

Reflecting on the vision given to St. Joseph in the Gospel of Matthew, Pope Francis said that "He dreams of the miracle that God fulfils in Mary’s life, and also the miracle that he works in his own life: to take on a fatherhood capable of guarding, protecting, and passing on a material and spiritual inheritance."

Pope’s General Audience – January 22, 2025

Wednesday, January 22, 2025

Pope Francis

Pope Francis

Pope Francis continued this cycle of catechesis on "Jesus Christ our Hope." Reflecting on the Angel Gabriel's greeting to the Virgin Mary at the Annunciation, he said that "The 'Almighty,' the God of the 'impossible' is with Mary, together with and beside her; He is her companion, her principal ally, the eternal 'I-with-you.'"

Pope’s General Audience – November 27, 2024

Wednesday, November 27, 2024

Pope Francis

Pope Francis

In his weekly catechesis, Pope Francis reflected on the fruits of the Spirit. Beginning with Joy, he said that "not only is it not subject to the inevitable wear of time, but it multiplies when it is shared with others! A true joy is shared with others; it even spreads."

Pope’s General Audience – November 13, 2024

Wednesday, November 13, 2024

Pope Francis

Pope Francis

In his weekly catechesis, Pope Francis reflected on how the Holy Spirit empowered the Blessed Virgin Mary to become the Mother of God.