In our Catholic Christian tradition we’ve been blessed with many role models for holiness in our saints. But sometimes it can be difficult to keep them all straight.

In this series, “Telling them apart,” I am presenting some side-by-side comparisons in order to help us keep track of commonly confused saints.

Pop quiz: Can you name a female Canadian saint canonized by Pope John Paul II who lived in Montreal back when it belonged to France and founded a religious order which was not only one of the Catholic Church’s first uncloistered orders for women but also had a profound impact on modern Canada?

Hint: Her first name is Marguerite.

It’s a trick question. That description could fit both Saint Marguerite Bourgeoys, the first Canadian woman to be canonized, and Saint Marguerite d’Youville, the first native-born Canadian to be canonized.

So let’s take a closer look at two pioneering Canadian women!

Marguerite Bourgeoys, CND (1620-1700)

This Marguerite grew up in Troyes, France. At the age of 20, she experienced a religious conversion which inspired her to dedicate her life to the service of God. Although she tried to join more than one religious order, she was denied entry. It seems God had other plans.

In her town was a convent of the Congrégation de Notre-Dame, which focused on serving the poor through education. Marguerite joined a group of local laywomen who worked with the nuns, and because of her involvement with the convent in Troyes, Marguerite met the founder of the new settlement of Ville-Marie (later called Montreal) in New France when he came to visit his sister, who was a member of the congregation. He invited Marguerite to take charge of education at Ville-Marie, and in 1653, she left France for a very different life.

However, when she arrived, Marguerite found there were not enough school-age children for her to teach, so she spent the first few years working alongside the other settlers and teaching the women of Ville-Marie in their homes.

At last in 1658, she opened a school in a disused stable, accepting both boys and girls as students in a time when they were normally educated in separate institutions. It was Montreal’s first school, and it would probably also be fair to say that this was Canada’s first co-ed public school.

That same year she returned to France to find more women willing to join her in her work. The four women lived together with common prayer and meal times and taught not only in the school at Ville-Marie but also travelled throughout the countryside, wherever they were needed. And thus began what would become the Congrégation de Notre-Dame de Montréal. Unlike the one in Troyes where the women were tied to a convent and had limited contact with the outside world, Marguerite’s new community had the freedom to travel. She felt it was important – especially in the very different circumstances of ministry in New France – for the women to have this freedom. But the idea of a religious community of women who were not confined to the cloister was a new and disconcerting one for many people of that time, and Marguerite fought successive attempts by the local Catholic hierarchy to turn her congregation into a more traditional, cloistered one. She made two more trips to France to defend the character of the community, including one in which she met with King Louis XIV in 1671 and returned to Ville-Marie with letters patent – the royal, legal backing for the order’s foundation (as opposed to the canonical one, which came in 1676). And this in a time when an Atlantic crossing could take up to three months!

19th-century painting of the Congregation of Notre-Dame of Montreal by Henry Richard S. Bunnett (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The community continued to expand. Along with recruits brought back from France, Marguerite was joined by local women, not only those of French descent but also native and English women. They insisted on free education for all, inspired by the revolutionary thinking of St. Pierre Fourier, who had been convinced that education was the key to improving the lot of the poor. And though their students were educated in the Catholic faith first and foremost, they also received basic schooling in reading, writing, numbers, and practical skills.

The sisters also took under their wing the “Filles du Roi”, young women sent to New France to marry and start families, not only vetting their future husbands but also providing them with a supportive community and teaching them practical skills necessary for wilderness life.

An interesting story is told about the final days of this “Mother of the Colony”. A young sister of the community lay in bed suffering from a severe illness. They feared for her life, and Marguerite, now 79 years old, offered God her own life in exchange for that of the young sister. The next day, the sister’s health began to improve dramatically, while within a few days, Marguerite fell ill with a fever and soon died.

Portrait of Marguerite Bourgeoys taken the day after her death by Pierre Le Ber (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

For over 350 years, the Congregation of Notre-Dame have carried on Saint Marguerite’s legacy of empowering women, children, and the poor through education, thereby creating stronger families and a better society in Canada and beyond. And in 1982, Pope John Paul II declared Marguerite Bourgeoys the first female saint of Canada.

Her feast day is January 12.

Portrait of Marguerite d'Youville by James Duncan (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Marguerite d’Youville, SGM (1701-1771)

Marie-Marguerite Dufrost de Lajemmerais was born in New France in the town of Varennes (now a suburb of Montreal) to an aristocratic French family. In 1722, she married the dashing François d’Youville, a young fur trader who supplemented his income through the illegal sale of alcohol to the local native population.

Married life was not a happy one for Marguerite. Her husband was away for months at a time, she lived with a mother-in-law who made her life miserable, and four of her six children died in infancy. When François died in 1730, he left her with debts and two small children (Marguerite was also pregnant with their sixth child who died only five months after his birth).

But the hardships she endured during these years nourished an already deep spirituality, and throughout her life Marguerite had an intense devotion to “God the Eternal Father” and a profound trust in Divine Providence.

In 1737, she decided, with three other women, to create a home for the poor in Montreal. Despite their caring and compassionate work, the people of Montreal did not look kindly on them. The involvement of women in public social work was seen as something radical, and most people disapproved. They were mocked by family, friends, and even the poor themselves, who called them “les soeurs grises” or “the grey sisters”. “Grise” not only meant “grey”; it was also a slang term for “drunk”.

Undeterred, they continued their work, and in 1747, the sisters were invited to take over the failing General Hospital in Montreal, which had been founded by a religious order of brothers in 1695. Hospitals in those days were not only for the care of the sick but also the poor and the elderly. One major change that the sisters instituted was that they opened the doors of the hospital to everyone in need. Under the administration of the brothers, it had been open only to men, and there was no provision for poor, sick, and elderly women in Montreal.

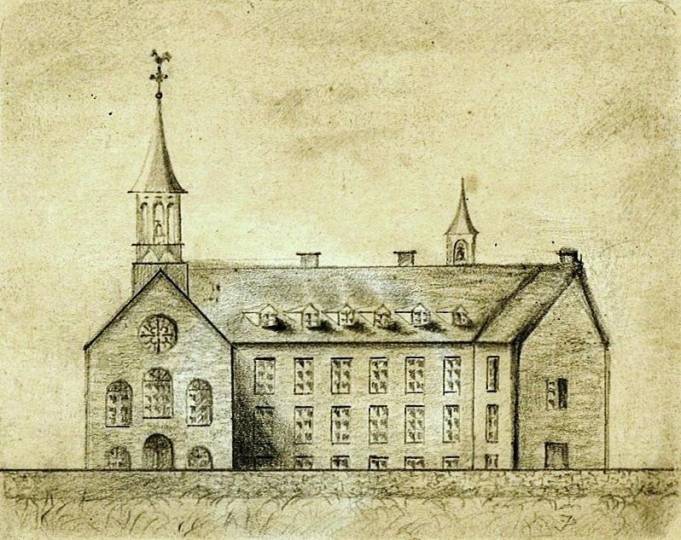

18th-century drawing of Montreal's General Hospital (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

In 1753, the sisters received the royal permission they needed to form themselves as an official religious community, and they received canonical approval from their bishop in 1755. Their official name was the Sisters of Charity of Montreal, but they continued to call themselves by their old nickname, “The Grey Nuns”, as a mark of humility.

Marguerite was a capable leader and administrator. The sisters and the hospital flourished under her direction despite the turmoil of the Seven Years War (1756-1763) and the upheaval of losing many of their friends and family who returned to France rather than live under British rule. And in 1765, they witnessed the destruction of the General Hospital. As the flames consumed their home, so great was Marguerite’s trust in God’s Providence that she led them all in singing the Te Deum (a traditional hymn of praise and thanksgiving). And then they rebuilt.

After Marguerite’s death, the order continued to thrive, expanding in the 19th and 20th centuries to missions in Western and Northern Canada and in the United States, always seeking out the poor and the suffering, providing healthcare and other social services which we in this modern age take for granted. In 1844, they travelled further west than any female religious had gone before in Canada, and as part of their ministry, they opened a house for the sick on the banks of the Red River which became Saint Boniface Hospital – the first hospital in Western Canada.

Because of her insistence on helping anyone in need with no restrictions, at her beatification in 1959, Pope John XXIII named her “Mother of Universal Charity”. When she was canonized in 1990, she became the very first Canadian-born saint.

Her feast day is October 16.

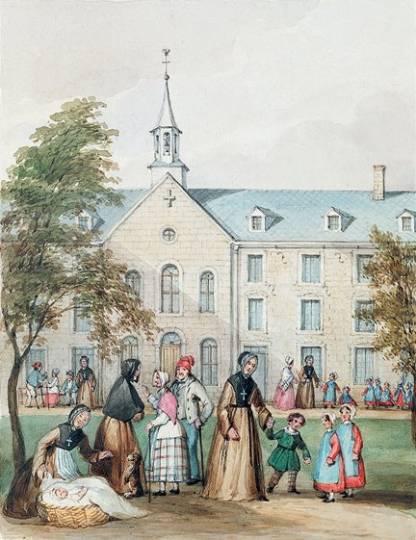

19th-century illustration of the Grey Nuns of Montreal by James Duncan (Source: Wikimedia Commons)