Last week we learned how the idea of Liberation Theology became an ideology, but saw how, officially, the Church did not condemn it, per se as a theology. This can be seen in the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith document

Instruction on Certain Aspects of the Theology of Liberation, issued in 1984 and signed by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger.

If Liberation Theology had its roots in the meeting of Latin American Bishops in Medellin, Colombia in 1968, it had a revival in 2007. This time, Latin American bishops met under Pope Benedict XVI at the Brazilian

Shrine of Aparecida. Its legacy is the “Aparecida Document” (

here in English), which intimately involved the Archbishop of Buenos Aires, Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio (who became Pope Francis). While the document makes no explicit reference to “liberation theology,” it does strongly promote the Church’s “preferential option for the poor.” It promotes a model of “see, judge and act” in the face of injustice and poverty, but insists “seeing” means through the eyes of faith; through the eyes of discipleship.

Since Bergoglio’s election as Pope Francis in 2013 some have suggested that the Aparecida document has become the roadmap for the Universal Church. The particular experience of the Latin American Church —of a people colonized, oppressed, impoverished, trampled on and abused— has found a voice through the Universal Pastor. Pope Francis often refers to the

descartados, the throwaways, who, for him reflect the face of Christ and the

pueblo fiel, the ones who can teach us much about faith, solidarity and community.

Pope Francis would call it

Teología del Pueblo or “Theology of the People.” He often warned the people of Buenos Aires against separating God from the Church, the Church from Christ and Christ from his people. As Pope he has frequently cautioned us against all ideologies.

Bergoglio is not the only Church leader to develop Liberation Theology in recent years. The Prefect for the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith is German Cardinal Gerhard Müller. In 2004 he co-authored a book with Gustavo Guitérrez entitled, “Taking the Side of the Poor — Liberation Theology”. At the book launch, Cardinal Müller said that

“whoever wants to be a Christian is obliged to do something so that this earth becomes livable for all.” Both authors said that Liberation Theology is a response to the

“conscience against abuses, an effort to put an end to injustice.”

Recently Rome seems to be recognising the gifts of Liberation Theology: emphasis on the poor at the centre of the Gospel, work to eradicate the structures of oppression and the hope of liberation in Christ Jesus. Last year's beatification of El Salvador's Archbishop Oscar Romero is another testament to this. Romero’s postulator Archbishop Vincenzo Paglia said that what was a delayed process “had been unblocked,” and he added that it was Pope Benedict XVI who unblocked it.

It is inaccurate to label Liberation Theology simply as Marxist. It is also inaccurate to label Romero as a liberation theologian. Romero’s former secretary, Msgr. Jesús Delgado has said that,

“Romero never went to their congresses, nor published books with them, nor quoted them in his speeches and homilies.” Romero

“adhered to the doctrine of the Church.” In a way, Romero did the same as Bergoglio and many Latin American leaders in the face of oppression, violence and injustice: He consistently called on political leaders to work for the people. The goal was not to submit governments to the will of the Church, but to be a moral compass. The Church must give voice to those who have no voice if it is to be faithful to Christ, even to the point of being killed as Romero was when he preached a “conversion to Jesus and a personal encounter to Jesus.”

In a January 2015 interview for the book

Papa Francesco: questa economia uccide (“Pope Francis: This Economy Kills”), Pope Francis said that love for the poor is not Communism. He said that his concern for the poor is not a novelty, but that

“it stems from the Gospel and is documented even from the first centuries of Christianity.” He joked,

“If I repeated some passages from the homilies of the Church Fathers in the second or third century, about how we must treat the poor, some would accuse me of giving a Marxist homily.”

Concern for the poor is part of the Gospel message and is prevalent in the tradition of the Church. Archbishop Romero and Pope Francis teach us that we should always remember this fact as we work for justice and move towards being a poor Church for the poor.

-

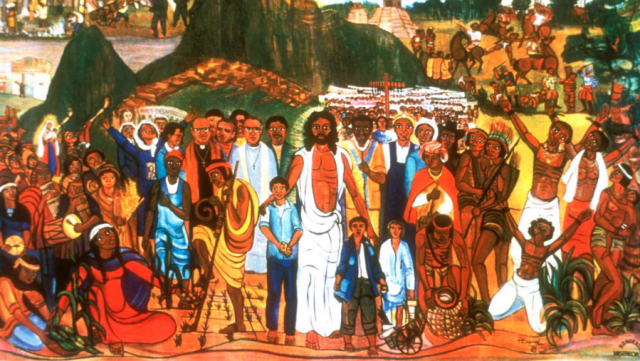

Image: "Station 15: Triumph of Life". From the “Stations of the Cross from Latin America 1492-1992” by Adolfo Pérez Esquivel of Argentina.

Every week, Deacon Pedro takes a particular topic apart, not so much to explore or explain the subject to its fullness, but rather to provide insights that will deepen our understanding of the subject. And don’t worry, at the end of the day he always puts the pieces back together. There are no limits to deaconstructing: Write to him and ask any questions about the faith or Church teaching:

[email protected]

Every week, Deacon Pedro takes a particular topic apart, not so much to explore or explain the subject to its fullness, but rather to provide insights that will deepen our understanding of the subject. And don’t worry, at the end of the day he always puts the pieces back together. There are no limits to deaconstructing: Write to him and ask any questions about the faith or Church teaching: [email protected]

Every week, Deacon Pedro takes a particular topic apart, not so much to explore or explain the subject to its fullness, but rather to provide insights that will deepen our understanding of the subject. And don’t worry, at the end of the day he always puts the pieces back together. There are no limits to deaconstructing: Write to him and ask any questions about the faith or Church teaching: [email protected]