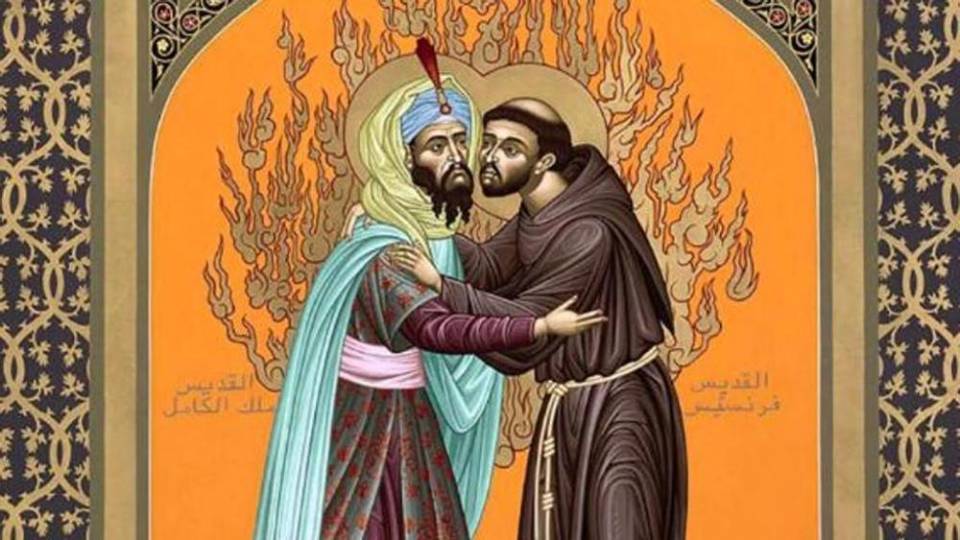

Eight hundred years ago this spring, St. Francis of Assisi and a single companion left on what may still appear as foolhardy an errand today as it did back then – to meet (and attempt to convert) the Muslim Sultan of Palestine, Syria, and Egypt: al-Malik al-Kamil.

As far as we can know based on the historical record, this was the first ever meeting of its kind. Never before had two such powerful (or holy) people from their respective faiths met in a spirit of peace and understanding.

The backdrop of the visit was the Fifth Crusade and the siege of the Egyptian city of Damietta, located along a tributary of the Nile River and situated near the southern coast of the Mediterranean Sea. Though Francis had seen war between city-states before in his native Italy, nothing had prepared him for the sight of carnage on this scale. Obstinate Christian leaders refused to accept generous offers of truce and monetary reward from Muslim leaders; a fifth of the Christian army died of typhus in the squalid camps along the Nile while the siege dragged on. Saracen soldiers caught by Crusaders were mutilated; in revenge, Muslim galleys along the river hurled fire and tar at the Christian siege forces. When they disembarked, the Saracens were known to impale any women and children from the camp that got in their way.

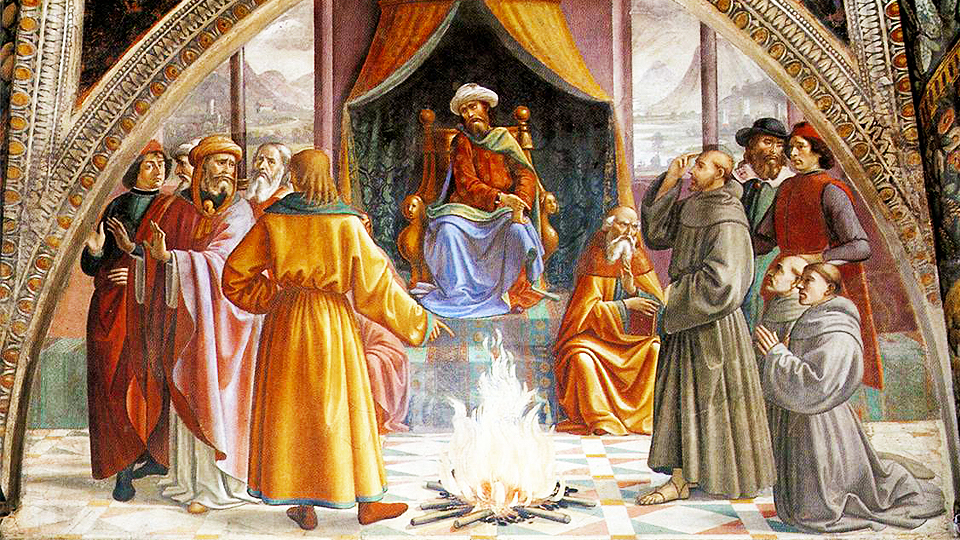

So naturally, when Francis and his companion, Illuminatus (one of his brothers with a rudimentary knowledge of Arabic), left the Christian camp for al-Kamil’s headquarters, it seemed nothing short of a suicide mission. That they even made it to appear before the Sultan at all speaks to our respective religious tradition’s shared heritage of consecrating oneself to the Divine; al-Kamil’s guards likely mistook Francis and Illuminatus for Holy Men in the same vein as Muslim sufiyya (Sufis), who wore a simple belted tunic similar to the type we still see Franciscans wearing today. They may also have expected that these men of faith were emissaries sent to continue negotiations on behalf of the Christian army.

Al-Malik al-Kamil was widely known as a pious and devout man. The nephew of the infamous Saladin, he received an excellent military education but was known to prefer the discipline of prayer to the sword. A strong believer in the One God, al-Kamil summoned his advisers to listen as Francis spoke of the story of salvation history, its culmination in the person of Jesus Christ, and a plea in the name of God for peace between the warring factions.

Perhaps unsurprisingly given his character, al-Kamil knew holiness when he saw it. Against the advice of his advisers – who recommended killing Francis, the usual punishment for Christians in a Muslim land who, though allowed to practice their faith, were legally subject to capital punishment should they try to preach conversion away from Islam – he spared Francis, even inviting him to spend a week in his residence as an esteemed guest.

While we know nothing of the content of the conversations between Francis and the Sultan, we do know that Francis and Illuminatus left a week later, untouched and unharmed. They were gifted ample provisions for their return journey, even refusing an offer of precious gifts (which impressed al-Kamil even further). They were not, however, unchanged.

Francis had left for Damietta with martyrdom on his mind; in a way, he truly hoped the Sultan would have him executed, so he could die what he deemed a glorious, saintly death. Instead, in the Crusader’s filthy camp he contracted the trachoma infection that would eventually leave him nearly blind and in constant pain for the rest of his life. With eyes oozing, irritated, and inflamed, it was a different kind of martyrdom than the one he envisioned but martyrdom nonetheless. The dialogue with al-Kamil seems to have changed Francis’ heart, too, challenging his assumptions about someone who had once seemed so “other”. Perhaps it was Francis, not al-Kamil, that needed to be “converted” after all.

Eight hundred years ago, St. Francis of Assisi imaged Christ for us in his ministry of encounter with people on the margins – even those on the margins that we ourselves may have created through our lack of understanding, cultural understanding, empathy. As I write about this fateful event,

Pope Francis is visiting the Arabian Peninsula, the “bridge” between West and East, where Christendom and the Muslim world meet.

Perhaps the lesson for us is that the “culture of encounter” Pope Francis seeks to foster has deep roots, inspired at least in part by his namesake. And that while much may have changed in the near-century since the Fifth Crusade raged and a Sultan met with a Saint, the

need for dialogue remains as important as ever.