In our Catholic Christian tradition we’ve been blessed with many role models for holiness in our saints. But sometimes it can be difficult to keep them all straight.

In this series, “Telling them apart,” I am presenting some side-by-side comparisons in order to help us keep track of commonly confused saints.

St. Augustine, Bishop and Doctor of the Church, is probably one of our better known saints. At least by name. But what do you really know about him? And can you really tell him apart from that other St. Augustine?

And did you know, strangely enough, that they both have famous legends involving children/angels?

Augustine of Hippo (354 - 430)

This Augustine is quite possibly the most influential thinker and writer in all of Christian history. (Ok, except maybe for St. Paul.) But if you know nothing else of him, you’ve probably heard his famous prayer as he struggled to turn his life toward God: “Grant me chastity and continence, but not yet.” Or the equally famous quote: “You have made us for yourself and restless is our heart until it comes to rest in you.”

Both come from the autobiographical account of his conversion (

Confessions), which has remained throughout the centuries an enduring and popular Christian classic. (I highly recommend it. It really is a great read.)

Augustine is a great saint for those of us (surely I’m not the only one?) who haven’t managed to figure out the whole holiness thing as children. It’s comforting to know that one of the greatest saints of the Christian tradition got things so spectacularly wrong for so long. As a young man, Augustine was, in a word, brilliant. He was also arrogant, proud, and ambitious.

Augustine was born in Thagaste, a city in the Roman province of Numidia (and in present-day Algeria). Although his father was a pagan, his mother, St. Monica, raised him in the Christian faith. But other influences, especially his own intellectual pride and arrogance, led him to abandon his mother’s religion for the more fashionable philosophy of the Manicheans (based on a belief in a cosmic battle between good and evil rather than an omnipotent God who is good), which Augustine saw as a more intelligent version of Christianity. He was also a slave to lust and lived with a mistress for many years with whom he had a child, his beloved son Adeodatus (who died tragically at the age of 16).

Through all her son’s waywardness, Monica kept up her prayers for his conversion, and though no one doubts that the power of his mother’s persevering prayer brought Augustine back to God, on the surface of things, it was not his mother’s influence and example which drew him to Christianity but his encounter with another great Father and Doctor of the Church: St. Ambrose.

Detail of a painting of St. Augustine (left) and St. Ambrose by Fra Filippo Lippi. Source: Wikimedia Commons

See now the mysterious workings of the Holy Spirit. Augustine was a brilliant orator and began to make his living as a much sought-after teacher of rhetoric (necessary for would-be politicians and lawyers) first in Carthage and then in Rome. His Manichean connections helped him secure a highly coveted job at the imperial court in Milan. Augustine’s career was made. He was a superstar. But in Milan he met the local bishop, a brilliant and fatherly man named Ambrose. Less than three years later, at the age of 32, Augustine was baptized as a Christian.

Of course there’s a whole lot more to the story, but you can read all about it in his

Confessions.

Once Augustine realized that Christianity was actually a very intelligent religion, he began to apply his vast intellect to understanding and helping others to understand the great truths of the Christian faith.

Returning to Africa, he was ordained a priest in 391. In 395, he became a bishop of the city of Hippo Regius, where he stayed until his death in 430, while Hippo was under siege thanks to the Vandals, who were doing their part to contribute to the breakup of the Roman Empire.

To say that Augustine’s thought had a great influence on Western Christianity is an understatement. He basically set the groundwork for everything that came after him, including the Protestant Reformation. And when you think about how much Christianity, and especially Protestant Christianity, has influenced the Western world and brought us to where we are today, it’s pretty fair to say that our world would not be the same without St. Augustine of Hippo.

His feast day is celebrated on August 28.

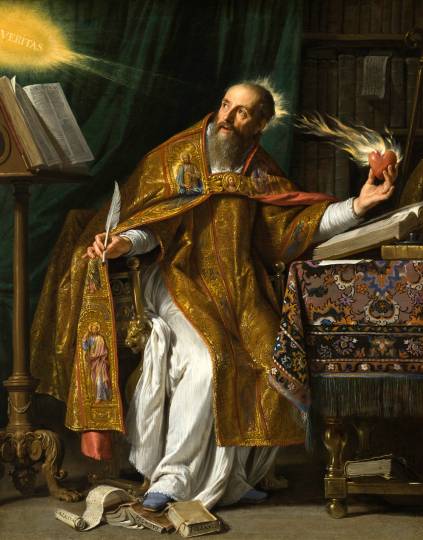

Saint Augustine by Philippe de Champaigne. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Augustine of Canterbury (? - 604)

Two hundred years after Augustine of Hippo penned his famous

Confessions, another Augustine was making his way with 40 companions on a mission of evangelization to what must have seemed to him the ends of the earth. Formerly a prior of a Benedictine abbey in Rome, he had been sent by Pope Gregory I to preach the Gospel in Britain.

St. Augustine is often called the “Apostle of England” and rightly so, but this epithet may be a bit misleading if you’re not up on your British history. So some clarification is in order.

In the time of the other Augustine, the one from Hippo, there were plenty of Christians on the island the Romans called Britannia, but while the first Augustine was witnessing the beginning of the collapse of the Roman Empire, this second Augustine was reaping the aftermath.

Much of the Christian population of Britain had been pushed west by invading tribes of Angles, Saxons, and Jutes from the region of modern-day Denmark and Germany. These people, who were now in charge of a large part of the island, were not yet Christians, and it was to them that Augustine was sent – specifically to King Aethelbert of Kent (in the southeast), possibly under the influence of his wife Bertha, who was a Christian. (Archaeology also suggests the quiet survival of pagan elements which resurfaced after the Romans’ departure, so perhaps the history is not so cut-and-dry as we are sometimes led to believe…but I digress.)

Augustine and his friends made some good inroads in their little corner of the island, with the conversion of King Aethelbert and thousands of his people. He was less successful, however, with the Christians already living on the island, who viewed him with suspicion and refused to acknowledge his authority over them.

Augustine established the bishopric of Canterbury and became its first archbishop in 597 (or thereabouts). Canterbury was the primatial see of all of England until the Reformation – meaning that the Archbishop of Canterbury had precedence and a certain amount of authority over all the other bishops in the country. Canterbury is now a see of the Anglican Church, and the Archbishop of Canterbury is still the spiritual leader of that Church.

St. Augustine of Canterbury’s feast day is celebrated on May 27.

St. Augustine of Canterbury preaching to King Aethelbert. From A Chronicle of England: B.C. 55 – A.D. 1485. Source: Wikimedia Commons

So what was that about children and angels?

An account of the life of Pope Gregory I was written by an unknown English monk around 700 AD. He tells a story (later expanded upon by St. Bede in his

Ecclesiastical History of the English People) of Gregory meeting some boys who had recently come to Rome (Bede says they were slaves). They were fair-skinned and fair-haired, beautiful to look at. Gregory asked them what people they were from, and the boys told him that they were Angles. Gregory, who apparently loved a good pun, responded, “Angeli Dei” meaning “Angels of God”.

And it was this encounter, according to the tale, which inspired him to send Augustine to save the souls of these people by bringing them the Christian faith.

(Usually, when the story is told nowadays, the pope’s reply is given as “Non Angli sed angeli” = “Not Angles but angels.” I guess that’s what happens when you have a millennium to work on a joke.)

Opus sectile panel in the Chapel of St Gregory and St Augustine in Westminster Cathedral in London. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Augustine of Hippo’s story was circulating in the Middle Ages, but where it comes from is anyone’s guess. And though it probably didn’t happen, it’s good to know it because it influenced the way he gets depicted in art sometimes. And anyway, it makes you think:

One day, so the story goes, Augustine was strolling along the beach contemplating the nature of the Trinity (as you do), when he noticed a boy running back and forth with a shell in his hand. The boy would dip the shell in the sea and then run back and pour the water into a hole on the beach. “What are you doing?” Augustine asked him. “I am putting the sea into this hole,” replied the boy. “But that’s impossible!” said the bishop. The boy, who was really an angel, replied, “It is easier for me to put the sea into this hole than for you to understand the mystery of the Trinity.” And then he disappeared.

Did you know?

This legend is why Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI has a scallop shell on his coat of arms. That’s one significance anyway. But there are two more: as a symbol of pilgrimage (read

“Telling them apart: Which St. James the Apostle?”) and as an element of the coat of arms of a monastery in Bavaria (

read more here).

Detail of Capriccio with the vision of St. Augustine in a ruined arcade by Ascanio Luciano. Source: Wikimedia Commons