[This blog comes from Jesuit scholastic Michael L. Knox. It was originally written as part of his studies.]

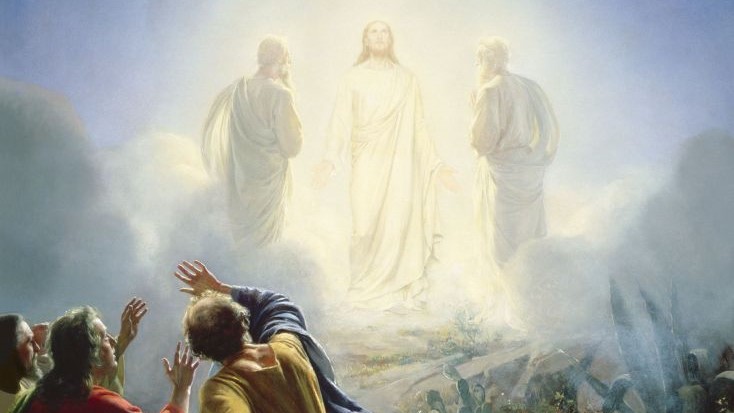

There is a love among medieval theologians such as St. Thomas Aquinas, Duns Scotus, or Hugh of St. Victor for what, to serve our purpose here, we might call ‘unity’, or ‘simplicity’, or ‘wholeness’. Qualities these men respectively identify in their writings about God, and a quality beautifully present in the Gospel reading of the day. For amidst the aesthetically pleasing images found within this Gospel narrative such as light, shining brightness, and mountain heights, we are presented a moment in the life and works of Jesus Christ that is a ‘unity’. First, the narrative ‘unites’ for us the messianic prophecies in the Hebrew tradition, with the living faith of early Christianity. Second, it helps to ‘unite’ the different aspects of our Lord’s life into a deeper understanding of who He is. And finally, the word invites a change to our own internal dispositions, on a profound and affective level, that we might understand the new sort of interconnectedness, or ‘unity’, that comes through Jesus Christ, between our God and our world.

Clearly, just as Christ himself was born into the Hebrew culture, with its various social and religious traditions, St. Matthew, or the “Mathian community” was not writing this account of Christ’s life in a bubble, far removed from this same context. The writings of St. Matthew, for example, rely heavily on the writings of St. Mark. More to the point, scripture scholars agree that, in fact, “the most striking aspect of St. Matthew’s gospel is how deeply steeped it is within the Jewish religious tradition. The evangelist’s focus, is the focus of Israel, namely, the coming of the Kingdom of God. Within this larger context, the Transfiguration, takes on a place of prominence as an event that unites this eager anticipation of Israel expressed throughout the Hebrew scriptures with Jesus Christ; who is presented as the true Messiah, the fulfillment of their expectations.

It is not by coincidence that Jesus brought three of his apostles into the mountains for His identity to be revealed to them, for the mountain is a, “traditional place of revelation” in the Jewish faith, as we see in the life of Moses (Exodus 24:1) or the life of Isaac (Genesis 22:2). St. Matthew’s description of Christ’s face that, “shone like the sun” is similar to the face of Moses descending from the mountain, “whose skin shone because he had been talking with God.” Except that in the Gospel, the very light of God shines from Jesus himself who is, somehow, God Himself. The appearance of Elijah and Moses with Jesus represent, for some scholars, the sign that Jesus is the 'fulfillment of the long line of prophets,' for others the ‘new Moses’ and still for others, the sign that Jesus is the “Law” (as it is epitomised in Moses) and the great prophet (as it is epitomised in Elijah). It is for these reasons that Peter, upon seeing all these things, cries out “Lord, it is good for us to be here.” Surrounded by a cloud when before God, is again in reference to the Hebrew notion of God presence on His Holy mountain in the account of the Ten Commandments. The very voice of God, proclaiming that, “This is my Son . . . He enjoys my favour . . . Listen to Him” is for many scholars in direct parallel with Matthew 1:11, when the baptism of Jesus by the Jordan is recounted, but is also a purely Jewish concept, for the “voice” of God often spoke to Moses (Exodus 24:15). Finally, the apostles respond to this voice by falling on their knees before Jesus in “fear” a disposition common in the Jewish faith, that can also be understood to mean “awe” or “wonder”. Thus, here in the account of Christ’s Transfiguration, St. Matthew unites the most ancient elements of the Hebrew narrative to Jesus Christ, and in doing so proclaims Jesus the Messiah and the Lord.

It is for this reason, that the text also reveals for us something of the identity of Jesus Christ. Specifically, it unites Jesus to God. For it is not the skin of Jesus that shone, as the skin of Moses had, from speaking with God but, rather, the light shone from Jesus Christ himself, “His clothes . . . dazzling white”(Matthew 17:2). In other words, the glory of God did not Shine on Jesus, as it did for Moses, but from Jesus, who is God, and mysteriously, God’s Son. A point that God himself declares from the ‘bright cloud’, with a voice so well known to the Hebrew scriptures, proclaiming, “This is my Son . . . listen to Him.” Finally, it is the “wonder” and “awe” normally reserved for God that the apostles offer to Jesus. He is truly for them the "Lord." The God of Israel is now both conceptually and actually united with their rabbi and is, in fact, God, as God’s son. We see Jesus then, in a sense, enthroned in all his glory as the psalmist writes when describing the Lord’s enthronement, "The Lord is King . . . Clouds of thick darkness are all around Him ... His lightnings light up the world . . . Light dawns for the righteous and joy for the upright of heart." (Psalm 97)

So we see now the beautiful way in which this text unites, so perfectly, the insights about God found in the Hebrew Scriptures to Jesus, and how this same text mysteriously unites Jesus to God Himself with the term

Son. All this being said, what are we to take from this Gospel passage to the altar of God and, with His blessing, into our lives and out into the world? For what does it mean to know that, as St. Paul writes, “at the name of Jesus every knee shall bend, in heaven and on earth, and under the earth . . . every tongue confessing that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father (Philippians 2: 10-11)? For I would suggest that, the Transfiguration, and indeed the Incarnation, invites us to a disposition in which we see the world in a new way.

First, that in every way, the world is as the Jesuit poet Gerard Manly Hopkins wrote, “. . . charged with the grandeur of God.” That somehow our world is infused, corrected, renewed, restored, and fulfilled in God’s Son. As such, our world-view might easily be effected in that all that we are, all that we have, and all that we do, is unified in Christ Jesus our Lord. What a sacred world we have my friends, and what a great responsibility we have to use for the sake of the One, who has given it to us, Who has restored it, and Who will come again. After the Transfiguration, I put to you, that we can never look at the world the same way again.

It is in Christ’s transfigured states, in His full divinity and His full humanity, that we gain a glimpse into the eschatological reality of the world that is to come for us in the resurrection. In this fact we find a second point for our own personal reflection. For the Transfiguration is part of St. Matthew’s narrative that seems to me most imaginative. Not that it is the most unlikely, but rather that it evokes fully our imaginations. We see the light and glory of what is to come for us all if we embrace Christ, and in seeing this, we can imagine ourselves in that light, there with the Lord. Is not imagination such a valuable tool in helping us to live good lives? Is it not our imagination which allows to envision the possibility of who we might be, who God loving yearns for us to be, and who we were created to be. After all, the Catholic moral life is not formed by simply learning a series of rules, but by realising, through Christ, our potentiality for holiness. A potential made most fully, and most “wholly” manifest in the light of the Transfiguration.

So as we approach the altar of God on this most holy feast, let us offer to him what we have learned today from the Gospel of St. Matthew, namely that: (I) we know His son to be the fulfillment of a promise made long ago and ascribed in the living history of Israel; (II) that deeper understanding of Christ which comes from recognising His sonship; (III) a special recognition that God is united anew to all created things; (IV) and that we are invited, and indeed ‘united’ to the life and works of Christ our Lord, so as to shine with a holiness that lies ready to be awakened in each of us.