In our Catholic Christian tradition we’ve been blessed with many role models for holiness in our saints. But sometimes it can be difficult to keep them all straight.

In this series, “Telling them apart,” I am presenting some side-by-side comparisons in order to help us keep track of commonly confused saints.

Every year on January 2nd we celebrate the feast of St. Basil and St. Gregory. But for the life of me, I can never remember which Gregory it is – Nyssa or Nazianzen (which I can never remember how to spell, by the way). I know one was the brother of St. Basil and one was his friend, but which one is which? And is one of them Gregory the Great? (Spoiler: the answer is no.)

So here is my attempt to help myself, as well as you, remember which Gregory is which.

Fresco depicting Gregory of Nyssa, by Theophan the Greek, in Anapausas Meteora, Greece. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335 – c. 394)

Would it be fair to call Gregory of Nyssa “Gregory the Least”? Of our three Gregorys he is the only one who is not a Doctor of the Church, though he is still considered a Father of the Church – one of the three Cappadocian Fathers. (Cappadocia is the central region of modern day Turkey where they were all from.) On his own, he seems to have done good work, but when you compare him to the other two Cappadocians (St. Basil the Great and St. Gregory Nazianzen), it does kind of look like the little brother tagging along. In fact, most of the images I can find of Basil the Great and Gregory Nazianzen together include not Gregory of Nyssa but another near contemporary who is also a Father and Doctor of the Church:

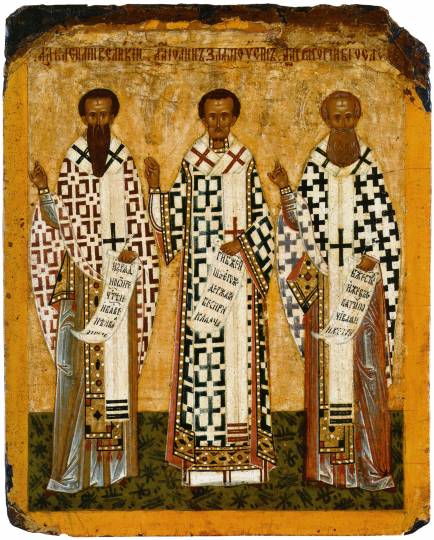

St. John Chrysostom. (This grouping is known as the Three Holy Hierarchs, though it’s sometimes mislabelled as the Cappadocian Fathers.)

It kind of makes me feel sorry for Gregory of Nyssa. Because he did make a valuable contribution in his time to combatting the Arian heresy (a rationalist form of Christianity which denied the divinity of Christ and was a powerful force in the early Church). And of all the Cappadocian Fathers, he was the most adept at using his training in Greek philosophy and turning it to good use in the Christian sphere. It’s true, though, that in his lifetime he was overshadowed by his older brother – but who wouldn’t feel inferior to a man of such zeal, energy, wisdom, and intellect as St. Basil? (It’s not for nothing that he’s called Basil the Great.) You might say that Basil used his brother like a pawn in his struggle to maintain control of the region he was supposed to have authority over as Bishop of Caesarea by making him the Bishop of Nyssa, apparently much against Gregory’s wishes.

Gregory was at first attracted to the worldly, secular life of a rhetorician, but under the influence of Basil and their older sister Macrina (also a saint), he discovered the joys of a more secluded life of devotion. And this kind of life probably would have suited his shy, scholarly, gentle disposition much better than that of a bishop, especially in 4th-century Cappadocia where he was constantly under fire from Arian factions, who had a lot of political power in those days.

It’s interesting to note that most of Gregory’s writings come from the period after Basil’s death in 379, as though he was picking up the anti-Arian/pro-Nicene torch and seeing it through to the finish line. As well as his important writings on the Trinity and the Incarnation, he is remembered as an influential member of the 381 Council of Constantinople, which affirmed and built upon the creed established at the Council of Nicaea in 325 (we know it as the Nicene Creed) and condemned the heresy of Arianism once and for all.

Gregory was a great admirer of the 3rd-century theologian Origen, and the influence shows in his work. So you might say that while some parts of Gregory of Nyssa’s theology are original, other parts are Origenal.

His feast day is celebrated on March 9.

Gregory of Nyssa from the Menologion of Basil II, a manuscript currently in the Vatican Library. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Gregory Nazianzen (c. 330 – c. 389)

Like his namesake and fellow Cappadocian, Gregory Nazianzen’s life was marked by the Arian conflict and the influence of St. Basil the Great.

Born near the city of Nazianzus (near Aksaray in central Turkey), his father, whose name was also Gregory, was the bishop of Nazianzus. Because young Gregory was bright and his family was wealthy, they sent him off to Athens to get the best education available in those days. And there he became best friends with a fellow student called Basil.

Like Basil, Gregory was attracted to a life of quiet asceticism, and so he gladly joined the new monastic community his friend had started. But as much as Gregory wanted it, it was not to be. His aging father asked for his help at home, and so Gregory, submitting to the wishes of his parent over his own desires, consented to priestly ordination in Nazianzus, assisting his father and doing what he could to support his friend Basil, who was waging an all-out battle against the Arians theologically and politically.

As he did with his brother, Basil attempted to put his friend in a strategically useful bishopric – a poor, dusty, way station of a town called Sasima. Gregory did not want to go to Sasima or be a bishop (and there is no evidence he actually went) and took great offence. This disagreement caused a rift between these two great friends which never healed.

Icon of the Three Holy Hierarchs, from Veliky Novgorod, Russia. Left to right: St. Basil, St. John Chrysostom, St. Gregory Nazianzen. Source: Wikimedia Commons

With the death in 378 of the emperor Valens, who had been a strong supporter of the Arian cause, things were looking up for believers in orthodox Christianity. And when Basil died only a few months later, they looked to Gregory Nazianzen for leadership. He was invited to Constantinople – the capital city – to provide spiritual support for the non-Arian Christians living in the city. Constantinople was a city divided, and Gregory had to endure conflict and even physical violence from the Arian faction. But in 380, the new emperor, Theodosius, arrived in the city, expelled the Arian bishops, and appointed Gregory Bishop of Constantinople.

The people of the capital city were used to polished and showy orators, so they were not immediately drawn to Gregory’s unprepossessing appearance, but he soon became a popular speaker – preaching mainly on themes related to the dual nature of Christ and to the Trinity since these were major points of controversy at the time. One member of his congregation was a clever young man named Jerome, who later also became a Father and Doctor of the Church.

He was elected to preside over the Council of Constantinople in 381, but his enemies challenged his position as Bishop of Constantinople on technical grounds. Tired of conflict and not wanting to be a cause of further division in the Church, Gregory immediately resigned a position he had never wanted in the first place. He returned to spend a quiet life at last at his birthplace near Nazianzus writing poetry.

Gregory Nazianzen is sometimes called Gregory the Theologian, and he is considered one of the most important writers and thinkers of the early Church. His teachings on the Trinity, and especially the Holy Spirit, have been very influential on later theologians.

He shares a feast day with St. Basil on January 2.

Second Ecumenical Council of Constantinople by Vasily Surikov. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Gregory the Great (c. 540 – 604)

This Gregory has nothing to do with the other two, thank goodness, so he will be a bit easier to keep straight. But here again we have a Doctor and Father of the Church. But this one lived in the West and was a pope. (This is the Gregory who sent St. Augustine of Canterbury to the new pagan peoples who had invaded the island of Britain.

Read more here.)

Like the Cappadocian Gregorys, this one also had to choose between a quiet, contemplative life and one of active public service. He came from a wealthy, influential family and started out at first on a public career but soon after decided to abandon it for a monastic life.

But like the other two Gregorys, he could not resist the call of public duty when it came.

This was a time of turmoil for Italy. Rome was no longer the great city that it had once been. What remained of the Roman Empire was now ruled from Constantinople, and even the administrative centre of Italy had moved north to Ravenna. A Germanic tribe called the Lombards (who subscribed to Arianism, incidentally) controlled much of Italy and moved to capture Rome. Under siege, Pope Pelagius II sent Gregory as his ambassador to Constantinople at the head of a delegation to ask the emperor for help (which he never got).

And that was the end of Gregory’s monastic aspirations. After six years in Constantinople, he returned to Rome as the pope’s assistant and chief advisor. And when Pelagius II died in 590, Gregory was elected to succeed him as Pope Gregory I. He tried to refuse and apparently even thought of running away but in the end accepted the responsibility. Although he had to leave the monastery, he did his best to live a life of monastic simplicity, even as pope.

As pope, Gregory was a bold administrator and a savvy politician, brokering his own peace with the Lombards (because the Byzantine authorities were useless), reforming the management of papal lands, and staunchly defending the primacy of the pope in terms of authority (on principle rather than for his own honour). But he was also conscious that the pope was the “Servant of the Servants of God” (the first pope to use this title), and it is said that when he died, the papal treasury was empty because he had given all the money to the poor (though some of it at least also went to pay off the Lombards and keep them out of Rome).

He was also a prolific writer. Two of his better known works are the

Dialogues, which contain stories of many early saints, including St. Benedict of Nursia, and

On Pastoral Care, which sets out his understanding of a bishop’s responsibilities.

Although he himself made no original theological contributions, his synthesis and comprehension of earlier Church Fathers had a profound influence on how those Fathers were understood in the Western Church during the Middle Ages. Not only did his writings greatly influence medieval thought and spirituality, but his administration of the papacy also laid the groundwork for the medieval understanding of the pope’s temporal and spiritual authority.

And because I know you’re wondering: Yes, this is the Gregory that Gregorian chant was named after, but he seems to have no connection to it in actual fact. But if you know how his name came to be attached to this liturgical style of music, please let me know!

His feast day is celebrated on September 3.

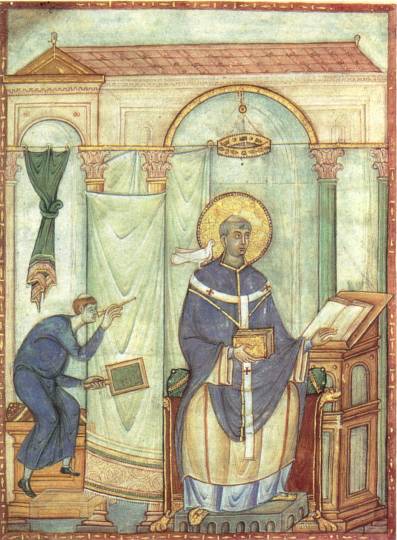

St. Gregory the Great is often shown with the Holy Spirit, in the form of a dove, speaking into his ear. This comes from a story about what his secretary saw when he peered through a curtain while the pope was dictating his homilies. From the Gregorblatt manuscript. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Still can’t remember which Gregory shares a feast day with St. Basil?

Me neither. Sometimes you just need a little trick to help jog your memory. So here’s what I’m going to try: If you can at least remember that Gregory the Great was a pope and that the other two were Cappadocian Fathers together with St. Basil, then you put the Cappadocians in alphabetical order. The Gregory closest to St. Basil shares his feast day. And who is Gregory of Nyssa? He’s the little brother who gets left out. Well, we’ll see in four months whether this works or not!

Bonus Gregory

Pope Gregory XIII (1502 – 1585) is not a saint, but he’s worth knowing because in 1582 he gave the Catholic Church a new calendar, which we call the Gregorian calendar (as opposed to the previous, Julian calendar – named after Julius Caesar). Most of the world follows this calendar today.